Public Space and Democracy in Mexico City: On the frontiers of gentrification

by Ricardo Nurko and Analiese Richard

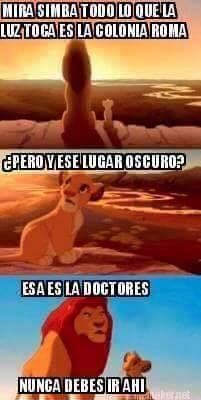

Pushkin Park is a liminal social space, located on the border between two central Mexico City neighborhoods: La Roma, a hotbed of cultural creativity and real estate speculation sometimes referred to as “Williamsburg South” and La Doctores, a less prosperous zone of government facilities like hospitals and courts, run-down housing blocs, and small-scale industry. The eastern limit of the park is Cuauhtemoc Avenue, a major thoroughfare that also marks the frontiers of gentrification. In the cultural geography of Mexico City, La Doctores is still viewed with disdain and suspicion by many residents of La Roma and other upscale neighborhoods on its western flank.

Source: Facebook (Humans of La Roma)

“Look, Simba. Everything the light touches is the Colonia Roma.”

“But what about that dark place over there?

“That is La Doctores. You should never go there.”

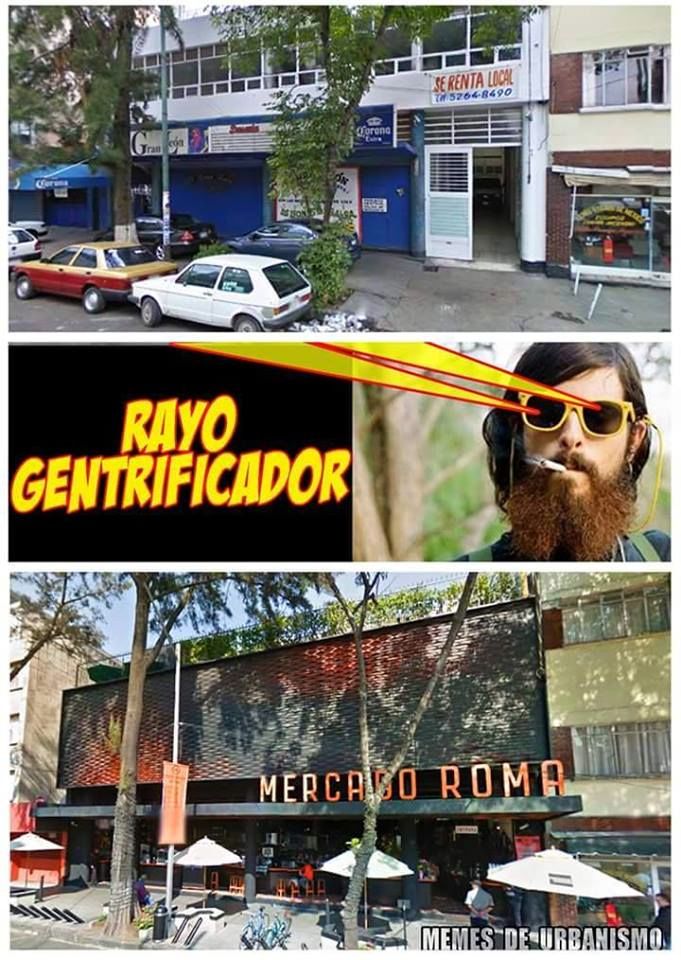

However, the “gentrifying ray” of Roma hipsterdom threatens to overflow this symbolic border very soon. As Mexico City’s central neighborhoods become more exclusive, public spaces like parks provide increasingly rare zones of encounter between people from different social classes and backgrounds.

Source: Facebook (Humans of La Roma)

The “gentrifying ray,” applied to a long-time neighborhood hangout, converts it into an upscale market hall catering to wealthy gourmands (mere blocks away from the neighborhood’s traditional working-class market, Mercado Medellin).

Pushkin Park’s status as a social frontier is the product of a combination of gentrification and planned urban development, propelled by real estate speculation and the presence of “territorial reserves” left behind by the 1957 and 1985 earthquakes as well as the de-industrialization of the urban core. In the 1990’s, the nearby neighborhood of La Condesa was progressively re-populated by a younger group of upper-middle class professionals, whose parents’ generation had earlier abandoned the central city for newer, more exclusive neighborhoods to the west. Young families began taking over the two large parks in the center of the neighborhood, Parque Mexico and Parque España, and a zone of hip shops and trendy restaurants sprang up in the surrounding area. Insurgentes Avenue, the second-longest street in the world (and a major 6 lane artery), originally marked the area’s eastern border and posed an obstacle to gentrification’s advance.

Source: Ricardo Nurko, based on Google Earth

Map showing present-day neighborhood borders.

Nonetheless, by the early years of the new millennium, the high demand for housing in the urban core and the cultural and culinary attractions of La Condesa were pushing that limit. By 2010, a rapid gentrification process was underway in La Roma, driving the eastern frontier all the way to Cuauhtemoc Avenue. Aside from these longitudinal corridors, La Roma is bisected by two major intersecting interior arteries, Orizaba Street (north-south) and Alvaro Obregon Avenue (east-west). Pushkin Park is located precisely at the point where Alvaro Obregon runs into Cuauhtemoc. In the median of Alvaro Obregon is a lineal park, with large shade trees, outdoor sculptures, and deteriorating fountains. Rumor has it that this park was the original target of the rehabilitation project that ultimately ended up being carried out in Pushkin. The story goes that AEP had the project all planned out, but because of an issue with political timing (a topic we’ll touch on in the next post), they were unable to undertake that project before the budget period ended. To prevent the funds from being wasted, AEP decided to apply them instead to Pushkin Park. This would not be the park’s first facelift—it had undergone several important transformations since it was first established in 1902.

Pushkin Park began as two separate lots. The first was designated by the city for a public market “or other municipal purpose” by the City Council during the planning process that created La Roma as a residential neighborhood. An adjacent lot was donated specifically for use as public space in 1913. However, the park was not officially inaugurated until after the Revolution, in 1920, when President Alvaro Obregon named it for Jesus Urueta, a well-known statesman and writer. While the park was to change names twice more over the next century, the literary theme would remain. A decade later, a playground was installed in the northern sections of the park, and it was renamed for Amado Nervo. In 1942, President Avila Camacho began a program of rent control in Mexico City that would have long-term consequences for the neighborhood. In later decades, as the housing stock deteriorated, landlords had little incentive to keep up their apartment buildings in the zone. The 1985 earthquake devastated La Roma and La Doctores, and landlords subsequently abandoned their properties. Many damaged buildings were taken over by squatters displaced by the disaster.

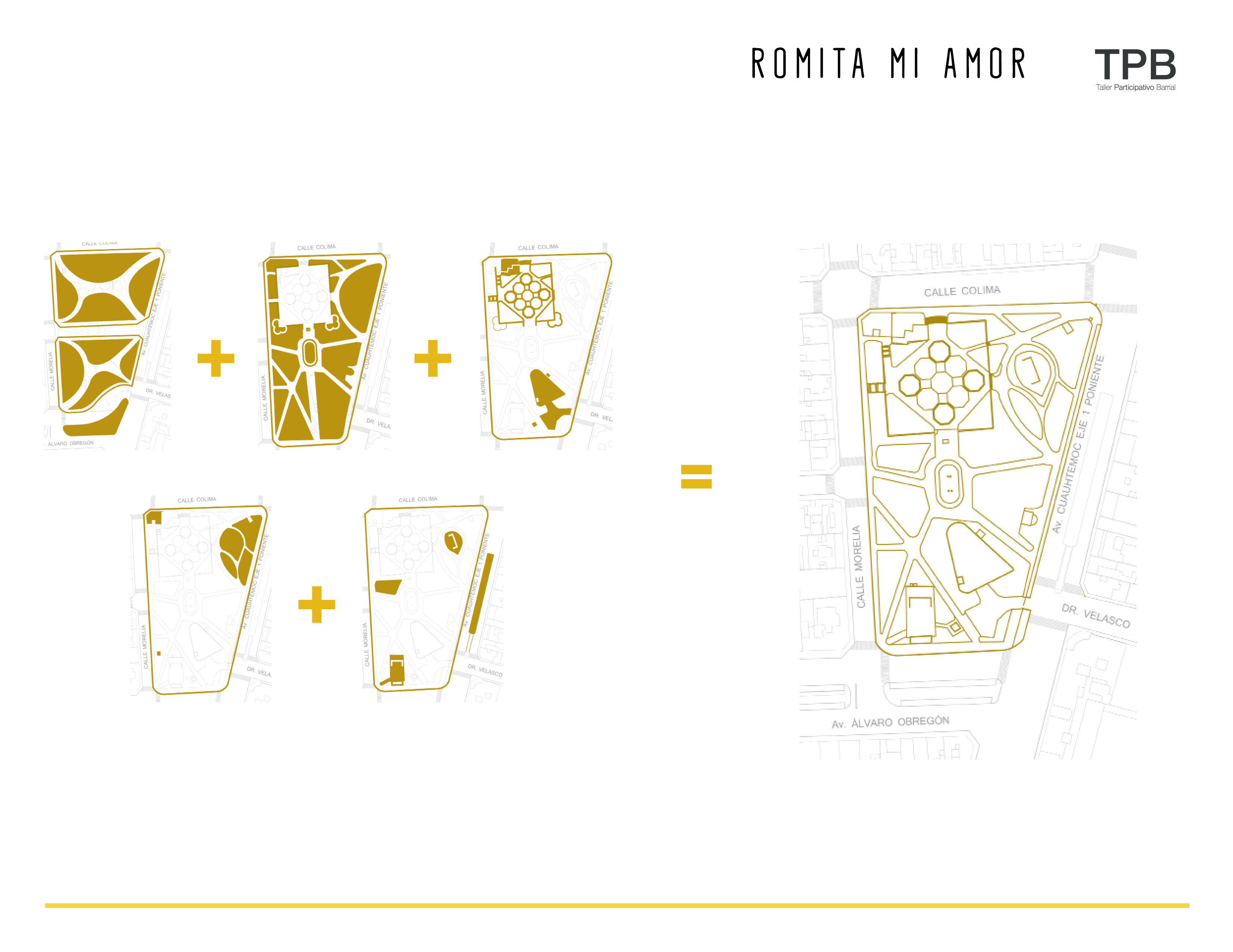

In the 1960`s the park underwent a complete redesign, including the unification of the northern and southern sections, installation of a small library and a central fountain. It also received the name it now bears: Alexander Pushkin Park. Over the next 20 years, a series of facilities came to be installed in the park (including a drainage facility, a police substation, a trash sorting facility, and seismic detectors) in seemingly random locations, with no integrated development plan. In other words, the park became a catch-all space for several neighborhoods, a kind of Frankenstein’s monster. This sense of disorder was magnified after the earthquake of 1985. After serving as a marshalling ground for search-and-rescue and humanitarian aid groups, the park also became the site of an open air market, or tianguis, that continues to saturate both the park and the surrounding streets on Sundays and Wednesdays (Post 5 will examine how informal commerce expanded in public parks and streets during the crisis period of the 1980`s, and how its political entrenchment contributes to current debates about public space in the city). Over the last decade, attempts have been made to re-activate the park by installing bathroom and a handball court. Until now, however, there had been no official study of the layout and functioning of the space as a whole. Its liminality contributes to its complexity, in terms of the functions that it has been assigned, but also in terms of its population.

Source: TPB report, Parque Alexander Puskin, available at http://issuu.com/tparticipativo/docs/2015-08-19_final_pushkin

Historical phases of development

There are further layers to Pushkin Park`s status as a liminal space. Gentrification doesn’t just mean soaring housing prices and gourmet restaurants on every corner. When central neighborhoods transition to upscale mixed residential and service zones, workers and customers flow in from other parts of the city. While it is true that La Roma has received a wave of residential migration from other parts of the city, the majority of its new population is actually service, retail, and construction workers who commute in on weekdays, and the upscale clientele from other neighborhoods who arrive in the evenings and on weekends.

This kind of “floating population” is also on the rise in La Doctores, but for slightly different reasons. The neighborhood is already home to a number of federal and metropolitan administrative facilities (legal centers and courts), as well as major public hospitals and health facilities that serve the entire city. Over the past several decades, this concentration has spurred the proliferation of private clinics, pharmacies, and health-related businesses in the zone. The government has plans to build more major administrative facilities in La Doctores in the very near future—an entire “Administrative City” (Ciudad Administrativa) ! Already, on any given day thousands of doctors, lawyers, patients, plaintiffs, and workers of all sorts pass through the neighborhood, and their presence gives rise to commerce (both formal and informal), which brings in yet more people. Pushkin Park is near three major Metro stations and two Metrobus stations that form the backbone of the area’s public transportation infrastructure.

Source: Ricardo Nurko, based on Google Earth

Pushkin Park in relation to La Roma and La Doctores

One park user we interviewed described the sensation of coming up out of the crowded underground station at Metro Cuauhtemoc and walking through the park on his way to work. “I feel like I can finally take a breath. If I have time, I like to just sit for a minute under this tree.” Our surveys found that a majority of the floating population that passes through Pushkin Park on weekdays comes from the far eastern part of the city, a zone where there is almost no green space to speak of. They spend several hours per day commuting on public transportation, and make their living far away from where they “live.”

This floating population almost never figures into official processes of citizen participation in urban planning. If they are taken into account at all, it is as consumers rather than as citizens. From our perspective, this raises important questions about democracy and public space. Who can appropriate public space, and in what ways? Whose responsibility is it to care for public spaces? In a megalopolis like Mexico City, where many people spend most of their waking hours in a place that is far from where they sleep, what spaces belong to them? As one young activist told us, “Mi colonia no es mi IFE,” my neighborhood is not just the address listed on my voter ID card.

Spatial practices are a vital part of citizenship. That’s why it’s so important to analyze complex, layered spaces like Pushkin Park that lie on the frontiers of gentrification. In fact, many of the most important battles for the meaning of democracy in Mexico City are being fought over forms of appropriating and governing public space. We’ll share more on these struggles in future posts about the controversial Chapultepec Corridor megaproject.