On Hope, Running and World-building: Striving for Social and Environmental Justice through Landscape Architecture and Ethnography

In three brief takes, Roberto Ransom reflects on his 2020 Master in Landscape Architecture thesis, advised by Gareth Doherty at the Harvard GSD.

“If we stop running, the world ceases to exist.”

Arnulfo Quimare. A champion long-distance runner, on the cosmology of his people, the Tarahumara or Rarámuri.

—

I. Foreword

The thesis explores the indigenous Tarahumara practice of long-distance running. My intuition was that this practice would be an entry point for navigating issues of conservation, water, and contemporary urban landscapes in the northern Mexican city of Chihuahua and its surrounding territory. At first, before this intuition, I defined this territory rather conventionally, according to economic, infrastructural, topographic, and hydrological networks. Yet, I slowly realized that my understanding of these networks and territory were incomplete unless I included the agency of the Tarahumara who existed in these entangled networks.

Running became the entry point for engaging the Tarahumara, both grounding my work and revealing from the specific task and shared experience. In many ways, I think this insight has revealed itself to be correct. Largely because the Tarahumara have so vehemently (yet seldom violently) resisted assimilation and extermination for what has now been nearly 500 years. In doing so, they have shown that their impressive endurance is not only as runners but as a culture and keepers of an alternative worldview. The Tarahumara embody, extraordinarily, what nonwestern and non-capitalist human agency looks like. This functions at several levels: from the very concrete yet subtle scale of landscape interventions to a profoundly inclusive cosmology. I understand the dangers of placing them in this role and did so with hesitancy and even trepidation. But ultimately, what the Tarahumara do in a gentle but forceful manner is present testimony of hope amidst what is a very difficult situation. Through their example, they help us see the familiar in a new light, and in doing so allow us to reposition ourselves and question our roles in society.

“The Tarahumara embody, extraordinarily, what nonwestern and non-capitalist human agency looks like. This functions at several levels: from the very concrete yet subtle scale of landscape interventions to a profoundly inclusive cosmology.”

I like to paraphrase Wendell Berry who has written about how -it is only when you have faced the depth and breadth of a problem that there is room for hope-. In this case, attitudes towards the environment and our indigenous past are shifting among the general population in Chihuahua even if, simultaneously, the situation only seems to get worse. People are finding the capacity to be outraged amidst what has been a very challenging context full of historically perpetuated injustices that find most of us complicit. This outrage is necessary for hope and action to take place. In more pragmatic terms, it appears to me that this shift is perhaps, at least partially, in response to stark ongoing environmental and contextual pressures that demand nothing less than radical change.

Generally, I think our heightened awareness of Climate Change has highlighted processes that have been ongoing for a long time. Rapid urbanization and the industrialization of agriculture, forestry, and mining in Northern Mexico have resulted in a sharp decrease and even depletion of groundwater, deteriorated soils, and environmental degradation in general. Yet, in the specific, it has been a heightened awareness of social injustice that has revealed how banishment and dispossession of entire ethnic groups and populations have been part and parcel of this social and economic transformation. This massive demographic shift from the rural to the urban has once again disproportionately affected indigenous and female persons. When you see the statistics in femicide and assassinated indigenous environmental leaders this is appallingly clear. Yet these are precisely the two demographics with the most legitimate claim to agency for change in the current political environment in Mexico. Suddenly, with this framework we can approach problems like rural and urban poverty, drug cartels, and violence within the larger issues of climate and social justice. The beauty of these issues is that they exists at multiple scales, and it is at the community level that we find encouraging stories and individual examples of authentic leadership.

—

“(These processes) and the ensuing massive demographic shift from the rural to the urban have once again disproportionately affected indigenous and female persons…….Yet these are precisely the two populations with the most legitimate claim to agency for change in the current political environment in Mexico.”

—

II. Context:

I see several reasons for hope in the fraught context of Metropolitan Chihuahua, seemingly as discouraging as ever:

1. COVID has revealed the lack of public open space and protected lands in the urban fabric.

Open public space is inaccessible to large sectors of the population. It is for the most part concentrated in the wealthiest districts of the city at its urban core and towards the west. However, landscapes of ecological, cultural, and historical value exist within or adjacent to the 19,000 hectares of metropolitan urban sprawl of this sunbelt city. At times, these landscapes of value overlap informal urban settlements that belong to indigenous communities. In most instances, they occur within large privately held tracts of land. These landscapes exist in varying states of degradation or are often subject to outright destruction for developmental and extractive purposes.

2. Citizens are reframing outdoor spaces and environmental conservation as basic rights.

People are demanding access to places of recreation and expect these to be protected from degradation and development. Ironically, but unsurprisingly, the spaces being claimed as deserving of protection and conservation by common citizens are often controlled by the same political and economic elites who exploit and develop this land for private gain. This has ruffled some feathers among these sectors because they have been historically unaccountable for the environmental and social impact of their activities.

3. Grass-root activists – among them the collective Salvemos Los Cerros de Chihuahua - are speaking up.

They have implemented what so far has been a successful awareness campaign for the environmental protection of the mountain ranges enveloping the city and their riparian corridors.

The success of this campaign is thanks to the group’s autonomy to power and a constant engagement with local communities. they organize hikes, educational campaigns, and informal reforestation efforts. With outreach into the millions on social media posts, this group has gained the attention of local media and compelled the local government to engage. Thanks to budding alliances across social sectors, things are moving in the right direction. Perhaps the largest opportunity for short-term impact for this issue is the inclusion of Participatory Budget Projects for 2021 at the municipal level.

4. Thanks to the effort of SLCC and other grassroots associations, the Municipal government has included the designation of several emblematic landscapes in the city as urban environmental preserves into their working agenda.

Furthermore, SLCC has successfully notified the federal government of the existence of archaeological sites. Within these landscapes, there are sites tied to the Apache, Conchos, and Raramuri peoples who inhabited this land before Spanish incursions and modern Mexican settlements. However, the challenge is great, resistance to change is rampant across many of the most powerful political and economic circles.

5. Landscape infrastructure and public space are beginning to be recognized as essential for securing an improved quality of life today, but also as vital for achieving basic benchmarks for success into the future.

As a regional hub for automotive, aeronautical, and electrical manufacturing, Chihuahua is a city that depends economically on a globalized supply networks and investment. Addressing water security, robust regional infrastructure, and quality urban environments are now necessary to attract and retain investment and talent in a competitive global environment. This is compounded by climate change and demographic shifts that will only increase in the 21st century.

“A small but well-educated sector of public servants, academics, and private individuals are beginning to recognize the urgency of these issues. What remains to be seen is if this recognition comes with the acknowledgement that the necessary actions will require radical approaches.”

With the knowledge that these actions will go against the status quo and convenience of many of those now in power, there must also be true commitment to change. Which, if it is real and enduring, will come from empowering communities like the Raramuri, and from having the humility and foresight to integrate their deep knowledge and wisdom at the forefront of the new reality.

Amidst this environment, the role of designers and specifically landscape architects and planners should be that of catalysts for change. We are not merely technical advisors and executors of predetermined plans and policies. We should also leave behind the role of top down and isolated problem solvers. Instead, as well-rounded generalists, we can critique problematic dynamics and after learning and integrating multiple visions, propose multiscale approaches and solutions. We are equipped to assist with a large-scale diagnosis and simultaneously have unique tools to envision long-term plans that consider multiple factors and amplify the voice of the many agents involved.

—

III. Thesis

Process Embodied: running as world building

For the landscape architect, the Tarahumara cosmology and way of life are best understood and embodied by their practice of long-distance running. It is an entry point to a rich array of tasks that deal directly with place and contain a wealth of wisdom derived from a life embedded in natural processes. These tasks encompass agricultural practices, ceremonies, crafts, and social organization. They form a rich tangle of relations between human and non-human beings and their environment.

This work approaches the city as a microcosm of the larger territory. The socioecological network of the Tarahumara and urban infrastructure exist simultaneously in these different scales. Here is where the thesis proposes a taskscape along the Sacramento River and into the Nombre de Dios mountains in the city of Chihuahua. A taskscape, accord to anthropologist Tim Ingold, is an entire network of tasks or mutually interlocking dwelling activities that contain social and temporal dimensions. Just as the landscape is an array of related features, so the taskscape is an array of related activities. And as with the landscape, it is qualitative and heterogeneous. At the territorial level, the taskscape serves to understand the context of the project along a 250-kilometer-long section. This section intersects with an equally expansive temporal scale and highlights site conditions and dynamics that are replicated in a much more compressed scale in the metropolitan context of the city.

At the metropolitan scale and through a socio-ecological network, the taskscape aims to reconstitute the fragmented and heavily degraded high desert grasslands and riparian forest in the city of Chihuahua. This is realized by weaving a patchwork of native vegetation, horticultural fields, and spaces for daily life, organized, and maintained through tasks and elements of Tarahumara practice.

At the personal, corporeal scale, running is the task that links all other tasks. The beauty of a task is that it encompasses all aspects of Tarahumara life, sustenance, necessity, but also recreation which is intertwined with ceremony and social life.

By repetition and interaction, tasks become networks of communal living.

“The beauty of a task is that it encompasses all aspects of Tarahumara life, sustenance, necessity, but also recreation which is intertwined with ceremony and social life.”

A Seed for Hope

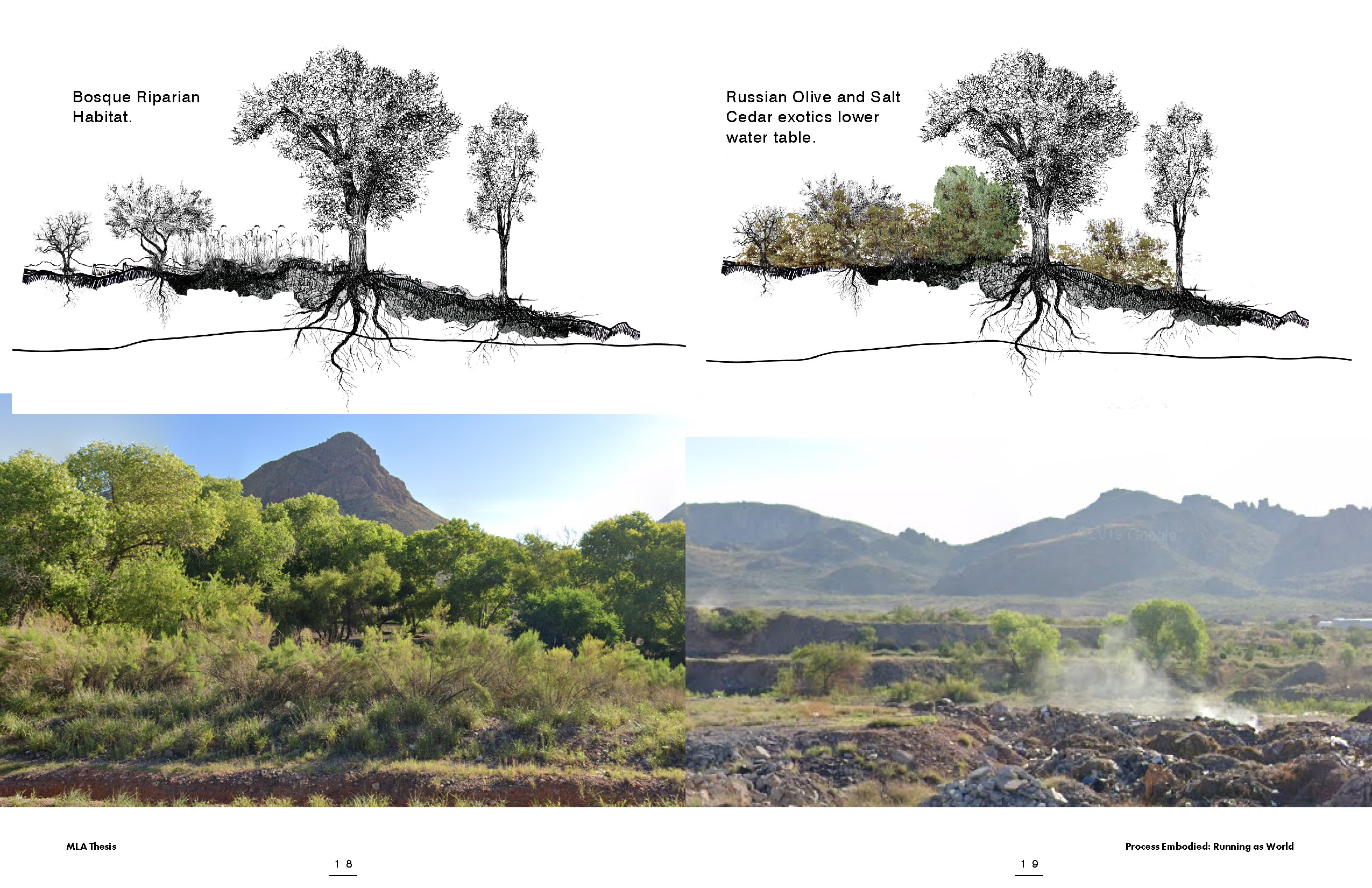

In Chihuahua, this Bosque and both riparian corridors have been fragmented and deteriorated In its most degraded segments, rubble and other infill material have been used to raise its banks and “protect” against flooding, with negative impact on the water table and floodplain, leading to entrenched arroyos and the demise of the Bosques. Because of cultural attitudes of mainstream incomprehension and ignorance towards both, Tarahumara settlements often coincide with degraded riparian corridor. This poignant reality is also the seed for hope. Some plant sketches are part of a collaborative study with painter Fernando Barba.

—

Roberto Ransom received an architecture degree from the Tecnológico de Monterrey prior to earning a Master of Landscape Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design in 2020. Roberto currently works at the landscape architecture and planning firm MVVA. He previously worked at JSa in Mexico City.

IV. References and further reading:

For a detailed essay on the concept of taskscapes:

Ingold, Tim. (1993) “The Temporality of the Landscape”, World Archaeology, 25(2): pp. 152-174

For a beautiful counternarrative to the techno-heroic hunter mythology (recommended by Mindy Seu, MDES 2019):

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, rev. ed. (London: Ignota Press, 2019)

For a masterful take on the socioecological complexity of Mexican forests:

Political Landscapes: Forests, Conservation, and Community in Mexico by Christopher Boyer (Duke University Press; 360 pages; 2015)

For the only written translation of Tarahumara cosmology and oral tradition:

Servín Herrera, Enrique Alberto. (2015) Anirúame: Historias De Los Tarahumaras De Los Tiempos Antiguos.

For a finely crafted travelogue and detailed description of mid-20th century Chihuahua and its history.

Jordán, Fernando. (2007) Crónica De Un País Bárbaro. Ediciones Del Azar, 2007.

For insights on transhumanism and post human models of environment:

Foltz, Bruce V., and Frodeman, Robert. Rethinking Nature: Essays in Environmental Philosophy.

Indiana University Press, 2004.

For a dated and partial description of Chihuahua and the US Mexico-Border (or lack thereof) that is nonetheless full of insight.

Jackson, John Brinckerhoff, and Helen Lefkowitz. Horowitz. Landscape in Sight: Looking at America. “Chihuahua as we might have been”. Yale University Press, 1997.

For basic concepts regarding grasslands in the Chihuahuan desert and climate change:

Carey-Webb, Jessica. (2020) “A Nature-Based Solution: The Chihuahuan Grasslands” The Natural Resources Defense Council.

For insight into the late 1990’s post NAFTA zeitgeist:

Millman, Joel. (1999) “Mexico Slowly Becomes Part of the American South”, The Wall Street Journal

For a case reference of Bosque restoration efforts led by Indigenous Nations:

Fullerton, W., and D. Batts. 2003. Hope for a Living River-A Framework for a Restoration Vision for the Rio Grande. Alliance for Rio Grande Heritage, Albuquerque, NM.

For Data insights into Mexican cities and their spatial and demographic growth patterns:

INEGI, Archivo histórico de localidades y Ciudades capitales, una visión histórico-urbana.