Navigating the Journey of Latinas to the United States

Carolina Sepúlveda

Master in Design Studies, Art, Design and the Public Domain, Harvard GSD

While migration from Mexico to the United States diminished in recent years, the number of migrants from Central America has increased substantially since 2010[1]. As a result, Mexico has consolidated as the primary transit route for migrants from the Northern Triangle countries, including El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The migration journey through Mexico is particularly violent for women[2]. At the different stages, women are subject to extortion, human trafficking, sexual violence, and even murder in the hands of gangs and organized crime groups. The paths and tactics used by women on the move present an unstable and shifting landscape reinforced by anti-migration policies and criminal groups’ presence along the routes.

Although the attention has been focused on Mexico’s northern border, it is at its southern border states (Chiapas and Oaxaca) where most of the crimes against migrants are committed. The introduction of new restrictive migration policies, such as Plan Frontera Sur in 2014 to secure Mexico’s border with Guatemala, has pushed displaced persons to follow more dangerous and isolated routes, some of them in territories controlled by organized crime. Additionally, border regimes have expanded to the interior of Mexico, Guatemala, Salvador, Belize, Nicaragua, and Panama, operating militarized strategies as part of transnational agreements, like the Merida Initiative (2007). While Mexican migration authorities are present at official border entries, most of the enforcements are carried out by inland checkpoints and along the highways that lead to Tapachula’s border with Guatemala.

The risk conditions of the migration journey are well-known by women. The more informed Latinas choose alternative routes to “La Bestia” train and travel by bus or private cars. In many cases, women contact smugglers beforehand and plan to get to different cities across the Mexico-Guatemala border, like Tapachula or Tenosique, in Mexico’s Chiapas state. Other approaches are avoiding sleeping at bus stations and migration shelters because they are hotspots for traffickers and smugglers looking for migrants to extort. Part of the essential support migrant Latinas rely on includes off-grid services to host, feed, and protect migrants, many of them run by local women.

The migration trip is carried out in the shadows of formality. Still, there are moments where immigration movements have been visible and gained a national scale, like the migrant 2018 Caravan that began in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, followed the coastal west route in Mexico and arrived at Tijuana. Furthermore, recent bills directed to limit asylum seekers and refugees’ flux enforced by the U.S., like the Zero-Tolerance Policy (2018) and the Remain in Mexico (2019), have had a direct impact on the formation of informal encampments at Mexico’s border cities. Matamoros, Piedras Negras, Ciudad Juárez, Nogales, Mexicali, and Tijuana, hold tens of thousands of migrants waiting for an asylum appointment in the U.S., including pregnant women, families with children, and LGTBQ individuals.

By presenting the experience of Central American women fleeing their countries of origin, the study displays a migration landscape of detention centers, control towers, fenced border walls, immigration court tents, migrant shelters, and informal migrant camps. Simultaneously, it underlines the solidarity networks Latinas rely on while on the move.

7

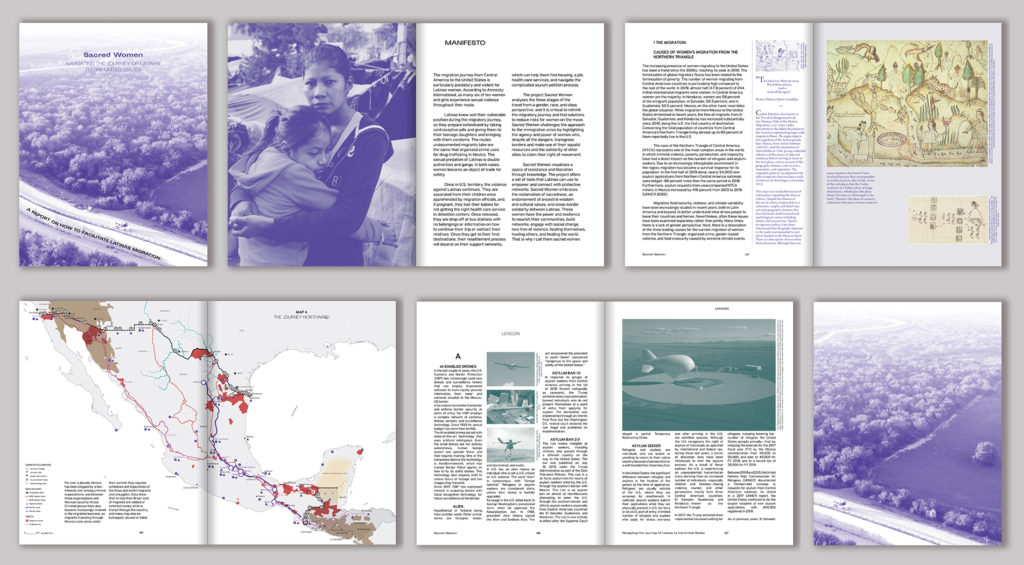

The research is consolidated in a 122-pages report that offers different reading entries to the project (image 1). It includes a manifesto (image 2), testimonies from women from the Northern Triangle countries (image 3), an academic essay (image 4), a series of cartographies that present the migration journey through Mexico (image 5), and a lexicon with keywords that are part of the United States and Mexico border and migration regime (image 6). The map of image 6 shows the transit across Mexico of migrants from the Northern Triangle countries, including Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. The blue line presents the primary route transited by women, and different resources along the path, including governmental immigration offices (symbolized with the letter i), and migrant shelters (triangles). The color red represents the threats, including the paths of La Bestia Train (segmented red line), and the reported dangerous zones (red areas). Lastly, the pink line presents the 2018 Migrant Caravan that departed from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, and arrived at the Tijuana port.

[2] Amnesty International reported in 2010 that the proportion of women and girls who are sexually assaulted over the course of their journey might be as high as 60%.