From the Periphery to the Palacio: The Urban Popular Movement and Democratization in Mexico

Evan Neuhausen

AMLO’s historic landslide victory in the 2018 elections marks a milestone in Mexico’s long transition from corrupt and authoritarian neoliberalism to democracy. This transition began in the early 1970s in the urban periphery of Mexico’s cities, where veterans of the 1968 Student Movement had moved to organize the urban poor. These organizations, at first isolated and small, coalesced into a national movement, the Movimiento Urban Popular (MUP). By the early and mid-1980s, MUP had successfully broken PRI’s control over Mexico’s urban populations, especially amongst the urban poor. Rapidly losing legitimacy and control over the urban poor in the face of the 1980s crisis, PRI split. AMLO, among those who left the PRI at this time to form the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD), is a product of this moment. Indeed, without MUP, it is difficult to imagine the PRI’s split, the PRD and AMLO’s subsequent rise to power, or even the triumph for Mexican democracy that AMLO’s victory–along with the PRI’s massive defeat–represents.

MUP is central to understand not just Mexico’s urban politics–that is, why urban areas have been strongholds for first the PRD and now AMLO’s MORENA–but how and why Mexico democratized. MUP not only won democratic electoral reforms, increased popular participation in urban planning and development, and basic urban services and infrastructure in Mexico’s urban peripheries, but also did so while maintaining autonomy from the state and–until the 1988 election–political parties. Beyond that, MUP was self organized, operating on principles of direct democracy and popular participation. These factors combined to create a democratic culture amongst MUP’s popular base; the difference between calling a neighbor compañera instead of señora. This alternative political and social culture was the result of a constellation of collective actions: meetings, marches, occupations of government offices and plots of land, payment strikes, housing construction, neighborhood planning, and the organization of popular cooperatives.

MUP’s creation of an alternative democratic culture in Mexico’s urban periphery was a key, if understudied, development in Mexico’s transition to democracy. Twenty years before PRI’s first defeat in a presidential election, and 40 before AMLO’s victory, MUP opened a space for democratic participation and consciousness in Mexico’s urban periphery. We can better understand contemporary urban politics and the democratizing processes that led to AMLO’s election by turning back to a movement that led to the flourishing of popular democracy amongst vast segments of the urban poor.

Origins, Crisis, and MUP’s 1980s Zenith

MUP was a federation of organizations with different degrees of activity, demands, levels of participation, number of members, and degrees of political consciousness. However, almost all of the organizations that comprised the movement shared the following characteristics: a democratic structure based on frequent assemblies featuring the participation of the popular base, combined with elected leaders who served short terms; an emphasis on organizational autonomy over close linkages with political parties and/or political currents (this changed with the 1988 election and creation of the PRD); the safeguarding of organizational independence against the state and its efforts of co-opting (Carlos Salinas’ anti-poverty program, PRONASOL, would successfully co-opt and neutralize many of these organizations); and a set of demands for both urban services and a more democratic distribution of power in Mexican society. The hundreds of organizations that composed MUP were often based within a specific territory and sometimes had differing demands; for example, a renters’ organization, while still part of MUP, may have had different organizational priorities than an organization based in an urbanizing periphery. MUP’s popular composition, democratic structure, set of demands that tied a lack of urban services to a critique of an authoritarian system of government, and its independence from the state made it a unique social movement in Mexico’s history.

MUP began in the aftermath of the 1968 Student Movement’s defeat. A group of ‘68 Movement veterans, identifying a scarcity of housing and urban services in Mexico’s medium and large cities, decided to move to Mexico’s urban peripheries and organize the urban poor. These movements, characterized by their Maoist ideology and militant practices, were especially strong in Durango and Monterrey. Their primary tactic was organizing land invasions, rapidly constructing housing, and subsequently demanding urban services. Luis Echeverría, President at the time, mostly accommodated these movements, allowing them to grow. In the late 1970s, MUP would recede some, due to its fragmented character and the López Portillo administration’s strategy of violent repression and eviction.

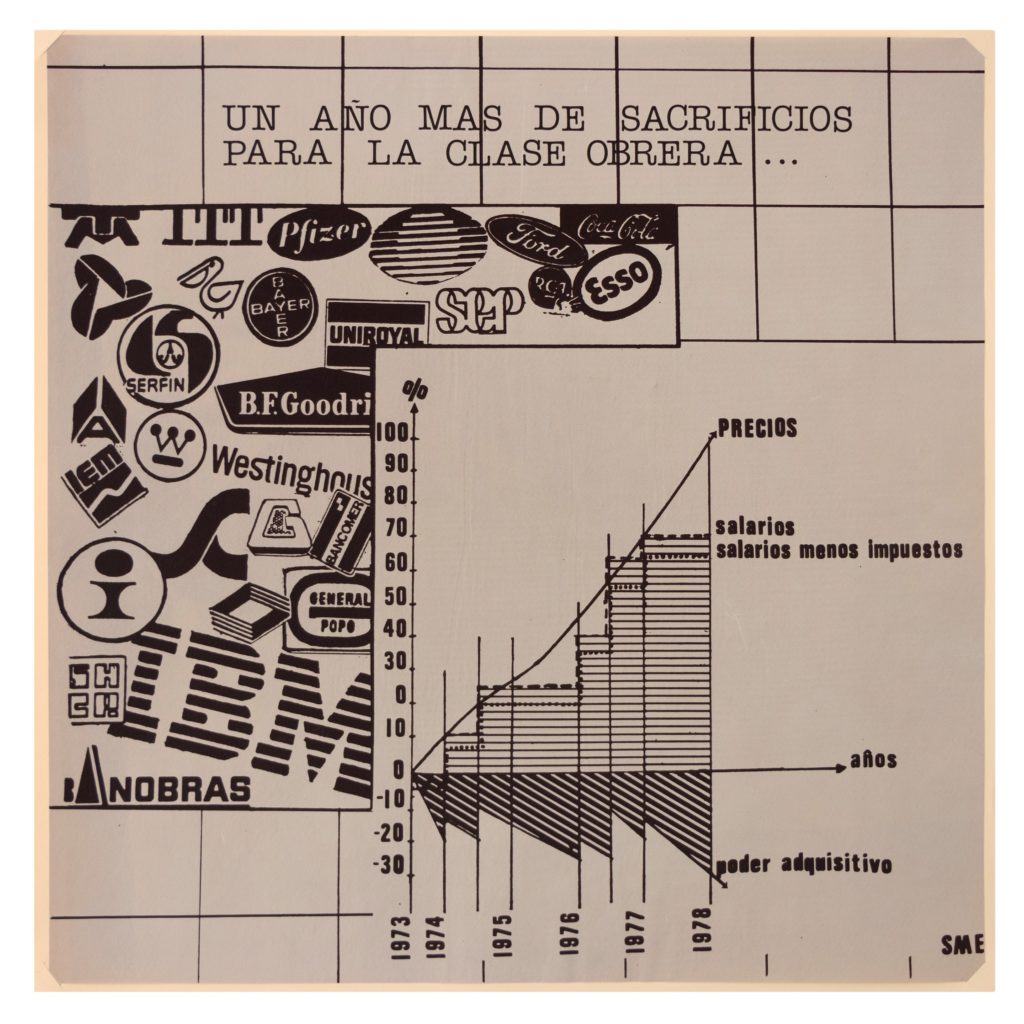

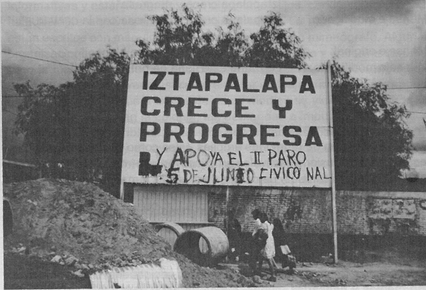

The period from 1979 – 1988 can be identified as MUP’s zenith. The movement exploded with the 1980s economic crisis and the PRI’s inability to effectively respond to it. Living conditions of urban residents plummeted as salaries—which had been declining since the 1970s–dropped precipitously for both middle class professionals and informally employed workers, who often lived in the peripheries of cities. Many could not find work: open unemployment averaged 11.5% between 1982 and 1985. At the same time, the price of basic goods rapidly rose. Between 1984 and 1987, prices of dietary staples in Mexico City increased exponentially: 754% for beans, 480% for eggs, 340% for milk, and 276% for cornmeal.[1] In this context, more than 500 rural-to-urban migrants were arriving in Mexico City daily, which due to a lack of planning, infrastructure, and the inability of the city to generate employment and income during the crisis, meant many of these new arrivals had to build new lives with neither assistance nor basic services from the state. MUP filled this void, creating networks of mutual aid between people building new lives on the urban periphery while demanding that the state provide basic urban services (electricity, drainage, schools, roads, clinics, and transportation) and democratically redistribute power.

In the face of a crisis that affected the urban margin most significantly, the PRI-controlled government, reeling from 1982’s near-default, implemented a program of severe austerity while prioritizing debt payments to foreign creditors over the basic needs of its citizens. Between 1984 and 1985, state spending was reduced by 12% on transport, 25% on potable water, 18% on health services, 26% on garbage collection, and 56% on land regularization.[1] Spending reductions reduced the state’s capacity to create and sustain the clientelist forms of co-opting that defined the PRI’s corporatism method of governing. Historically, PRI had been able to contain urban dissent within the CNOP, the organization created by the PRI in the 1940s to represent the urban popular class. This began to change in the 1970s when the Echeverría government instituted a series of administrative and political reforms to the CNOP designed to eliminate grassroots dissatisfaction and strengthen the link between the urban popular sector and local states. The reforms were poorly conceived and backfired, further encouraging people to turn to popular movements to pressure the state to meet their demands. Furthermore, with social spending rapidly reducing, the state could no longer reward communities and organizations with infrastructure and services for participating within its corporatist mechanisms. Urban populations had even less of a reason to participate in state-controlled organizations. The crisis thus created the conditions for MUP to expand: a rapid decline in living conditions, a quickly growing periphery that demanded the necessities of basic consumption (housing, schools, electricity, food, etc.), and a government–with its institutions for controlling and representing urban populations completely ineffective–unable to provide them. Hundreds of thousands of people, and especially women, who composed the majority of MUP’s popular base, joined MUP simply because it offered solutions to urgent and immediate problems in their lives.

By 1981, a national coordinating body was created for MUP, called CONAMUP. Representatives from over 100 urban popular movements from 14 states attended the founding meeting in Durango. Movements that had previously been isolated in their given territories now had an increased ability to press the government for its desired reforms while farther challenging its legitimacy. The creation of CONAMUP represented an extremely important advancement in the development of urban struggles; its creation began a new period in MUP, in both its capacity for mobilization and negotiation, as well as its demands. CONAMUP, which peaked in power between 1982 and 1985–when MUP’s focus would shift to reconstruction efforts in the aftermath of the devastating 1985 Mexico City earthquake–allowed organizations that had been previously isolated to strengthen their links, share experiences to build a collective knowledge and common identity, coordinate marches and actions together, and most importantly, collectively negotiate with greater force and power with the city governments. By 1984, around 60% of MUP was organized in CONAMUP, which had as many as 1 million members, with around 200,000 of them in Mexico City.

Politicizing the everyday, transforming urban social relations, and building movement culture

MUP went beyond subordinated protest and demand making, claiming participatory democracy and increased power in local development and planning decisions, which linked a critique of an undemocratic political structure with urban poverty and lack of basic services. At this level, it was a profoundly important movement in Mexico’s transition to democracy, both in Mexico City and nationally. In 1988, primarily on the back of urban populations organized in MUP, Cuahtémoc Cárdenas—running against the PRI’s austerity program—won the presidency, only to have it stolen by massive PRI fraud in support of its candidate, Carlos Salinas.

We can see how MUP played in an important role in democratizing both Mexico City and the country from the vantage point of top-down electoral reforms and government concessions to MUP’s demands for popular participation in planning in development. But the more difficult to see, but just as important, democratization happened from below, at the level of the everyday. It happened with hundreds of thousands of urban residents joining democratic movements that–at a local and neighborhood level–were enacting the society and the city they wanted to build in Mexico. Many of the movements that comprised MUP were able to create a democratic culture amongst movement members and in the territories they controlled. This meant that MUP opposed not only a negligent, authoritarian, and repressive state, but also the depoliticizing and isolating ideologies of technocratic rationality and privatized individualism.

The movement knew the importance of building an alternative way of seeing the world and one’s relations to other people in it. In 1984, CONAMUP released a document arguing that “to combat the penetration of dominant ideology in MUP, a popular political education is necessary in to support and elevate a level of consciousness and organization of the people, permitting the identification of our enemies from a perspective of revolutionary struggle.” MUP’s program of education was practical and derived from members’ direct experience in the movement. MUP achieved its goal of creating a popular, in contrast to dominant, ideology through a combination of its democratic structure–driven by popular participation–and its politicization of what had been considered individual and private issues. The hallmark of MUP’s political structure was the democratic assembly, which usually took place on Sundays. In these meetings, organizational decisions were made by vote, information openly circulated, debate was expected, participation encouraged, and differing political ideas accepted. Different committees, focused on different aspects of organizational work (e.g. a lack of potable water), would report on their progress and activities. In this way, information was created and circulated horizontally and openly, crucial for decentralizing power and decision-making.

Apart from practices of direct democracy and organizational decentralization, MUP’s collectivization and politicization of practices that had been considered private enacted a deepened idea of the political. MUP, focused on issues in the realm of consumption and the everyday, politicized the private lives of participants. Whether or not the lights worked; if there was food on the table or potable water; if your house was flooding; if you had to travel multiple hours on unreliable transportation to work; if your family had grown and you needed construction materials to build an additional room for your house-these all were signified as political and communal issues by the movement. A struggle for basic necessities, which had traditionally been relegated to the private sphere, erupted into public space, creating a relationship between political struggle and daily life.

Another example of how MUP’s demands–centered in the realm of everyday consumption of urban necessities–transformed social relations was the participation of women. While inexcusably almost completely excluded from movement leadership, women constituted around 60% of MUP’s base. This is not surprising. Women most directly lived the blows of economic crisis and the lack of urban services. As one women explained to anthropologist Gisela Espinos, “In the popular neighborhoods, the lack of basic services, the distance from the centers of consumption, education, health, and recreation, the lack of transportation, and the poverty all multiply domestic labor. Women exhaust themselves. The accumulated hunger and fatigue is what initially drives women to fight.”

Hundreds of thousands of women joined MUP, whose demands were directly relevant to their lives. It offered women the possibility of meeting other women struggling with the same issues and the ability to build social relations outside of the home. Women were the principle support and force of MUP. It was women, more so than men, who constituted the social base, the working groups, went to occupy public space in front of government buildings, fought on the front lines against evictions, provided the sustenance for marches while participating in them, and attended meetings. Yet they were not represented in movement leadership until the late 1980s in CONAMUP, as women demanded to be recognized and then filled roles as organizers and leaders.

The participation of women is another way MUP entered the realm of the private and remade social relations. Leaving the house to participate in a movement that defined itself as one of collective struggle gave many women the necessary sense a consciousness of being able to confront external enemies. This in turn could plant the idea of being able to confront problems in one’s own household and begin the battle of transforming relations within the family. Furthermore, meeting other women involved in the movement offered an opportunity to share experiences of oppression, both inside the household and the movement. In this regard, joining MUP created a new dimension in many women’s lives. Becoming conscious of a struggle opens new perspectives of information and experience for all participants, but especially so for women, who may have previously been isolated in their intersecting social positions as part of the urban poor and as a women.

MUP and Mexico’s Democratic Present

Of course, all of this paints a rather rosy picture of MUP. The depth of these transformations of social relations, achieved through democratic practice and the politicization of the everyday, varied both between organizations and within organizations themselves. The type of changes I have described may have only occurred in the most advanced and militant organizations that comprised MUP. Even when they did occur, they were fleeting. After the 1988 election, many of the organizations that comprised MUP linked themselves to the PRD, resulting in a decrease in internal democracy, autonomy, and movement culture. Furthermore, as the crisis passed and the living conditions in the urban margin became less dire, participation in the movement waned.

Yet participation in a socially transformative movement leaves a mark. For hundreds of thousands of Mexicans in the 1980s, many of whom were depoliticized and had only known political relations as authoritarian and domineering, MUP created an alternative vision, culture, and ideology of urban life. Beyond the democratizing electoral reforms MUP (in conjunction with other democratizing movements) forced PRI to make in 1988 and 1996, before finally winning representation democracy with Mexico City’s first mayoral election in 1997, we can see a truly democratic revolution at Mexico’s urban margin that transformed peoples’ lives. The triumph for Mexican democracy represented by the PRI’s catastrophic defeat in 2018 can be traced back to the urban periphery and the movements that built a democratic culture there. Democracy flowed from the periphery to the Palacio.

[1] Statistics from Diane Davis, Urban Leviathan, p. 266-67. Notes on Author: Evan Neuhausen is a researcher, translator, and archivist. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.