Public Space and Democracy in Mexico City: Who decides what is good for public space?

BY RICARDO NURKO AND ANALIESE RICHARD

This is part of a series exploring public space and democracy in Mexico City.

How can citizens have a say in the management of public space? Building a good strategy depends on mapping out the other actors involved and understanding the bureaucratic cultures and political timeframes of the many governmental entities that share jurisdiction over any given space. In Pushkin Park, multiple agencies with different scales and scopes of operation have power over particular aspects of the space, and there is very little communication or coordination among them. For citizen groups in Mexico, figuring out a way into that labyrinth can be a major obstacle.

Bust of Alexander Pushkin in the park’s geographical center.

A recent innovation in Mexico City governance is the creation of Neighborhood Committees (Comites Vecinales), unpaid volunteers elected directly by the residents they represent. Unlike representatives to the Legislative Assembly of the Federal District (ALDF), the committees are organized on a neighborhood scale (rather than delegation/borough) and do not participate in the official legislative process. Rather, they serve two intermediary functions. The first is to manage the local distribution of the Participatory Budget (Presupuesto Participativo), a fund composed of 3% of the total delegation budget. Residents submit annual proposals (common ones include maintenance of sidewalks, trees, and lighting, as well as park renovations), which are then voted on by their neighbors. Some neighborhoods have access to additional funds through another recent innovation: parking meters. The meters are operated by a private company, EcoParq, which is obligated to return 30% of the proceeds to the neighborhood in which they are collected. These are overseen by a separate citizen committee. The second function of the Neighborhood Committees is to facilitate citizen consultation processes related to public space and quality of life issues in their designated zones. Since the committees have only been around for two years, their role is still being worked out in practice. In La Roma, committees have been quite entrepreneurial both in seeking out resources to improve neighborhood facilities and in using their limited powers to protect their neighborhoods from crime, code violations, and some destructive forms of gentrification.

Children’s play area. Over the years there have been efforts to repaint with colorful murals, which tend to be quickly covered by graffiti. Parents and children avoid the slide, where indigents commonly sleep.

In fact, it was the President of the local Neighborhood Committee who sought TPB’s help in reviving Pushkin Park. The park was run-down and abandoned by both residents and authorities, so it was high on the list of neighborhood problems he wanted to tackle. He also knew that there were funds from both EcoParq and the city government designated for Pushkin Park, and that these funds had to be spent quickly before the current budget period closed (future posts will address how the temporality of budgets and elections impacts the management of public space in Mexico City). He approached the members of Taller Participativo Barrial (TPB), who agreed to carry out a participatory analysis of the space and the needs of its users, and to propose courses of action based on their diagnostic. A different contact informed TPB that a new master plan for Pushkin Park was already in the works at the Authority of Public Space, but no citizen consultation was being planned (Autoridad de Espacio Publico, or AEP, is an entity of Mexico City’s Secretariat of Urban Development and Housing, or SEDUVI, charged with carrying out renovation of public spaces. The selection of spaces commonly takes place at the level of the Mayor’s Office). TPB knew that in order for the park renovation to be successful, it would need to take into account the needs and preferences of users (including neighbors, commuters, informal vendors, and community groups). Expert and lay knowledge would need to be combined in a transparent way in order to generate viable solutions to the complex problems presented by the park.

The handball court is a good example of the complex functionality of Pushkin Park. In the mornings, the flat, protected court hosts Zumba classes attended by neighborhood women. In the afternoons, youth and adult men play handball. In the evenings and late afternoons, a small group of youth has taken over the space to smoke and sell marijuana.

TPB immediately set about trying to contact AEP, and after many setbacks were finally able to negotiate a small opening: AEP would hold off on formalizing their plans for Pushkin for a few weeks to allow TPB to carry out the study. They would allow TPB to present the results to city government representatives, but without any obligation to incorporate them into the final plan for Pushkin. In the best of cases, TPB hoped they would be able to demonstrate the importance of participatory planning, creating a precedent for future projects. In the worst of cases, they worried that their work would be dismissed whilst AEP used their study as political cover. That is, the agency could do whatever it thought most convenient with the space, meanwhile touting the “democratic” nature of the planning process.

Members of Taller Participativo Barrial and Romita mi Amor, a partner organization, prepare to carry out a participatory workshop with children in Pushkin Park.

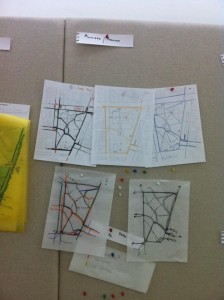

With time running short, TPB quickly put together a team of interns and enlisted the help of other citizen groups. The first step was to locate basic information about the space. Surprisingly, none of the city government offices TPB contacted could provide access to a topographic survey or basic plan of the park. Indeed, as far as they could ascertain, none of the multiple entities charged with managing and maintaining public space in the city have access to adequate or updated cartography of the spaces for which they are responsible. TPB thus combined information from Google Earth with intern-generated spatial surveys to create accurate base plans of the space, the built elements within it, and the patterns of use and movement through it.

Once a basic plan of the built elements was developed, use patterns were mapped.

Questionnaires were administered to a representative sample of park users to learn about the activities users commonly carry out in Puskhin and their impressions of the space. The historical layers of the park were researched and mapped. Apart from these expert-directed methods, TPB carried out three participatory workshops in the park to learn more about place-based identities and historical memory related to the park, as well as what alternative options users envisioned for the space.

These options were limited by the fact that this park also houses a sewer facility, a garbage recollection site, a small library, several seismic detectors, and a police surveillance booth, all badly deteriorated and haphazardly located. Different agencies—some federal, some municipal, some delegational (boroughs)—are responsible for each of these facilities. In other words, in addition to the overlapping layers of city government charged with administrating the space, any changes to those areas would have to be negotiated individually with yet other entities.

TPB interns organize data from spatial surveys and workshops.

Along the way, TPB discovered that in addition to the difficulty of negotiating with all these governmental actors to create a holistic plan for the space, there were important frictions with AEP over the meaning of “citizen participation.” Because it is on the border of two distinct neighborhoods, and located near major thoroughfares as well as public transportation routes, Pushkin Park is populated by a complex mix of users. For TPB, it was important to take into account the needs and perspectives of all (including residents, commuters, youth, neighborhood groups who use the park for meetings and activities, and informal vendors) in order to create a holistic plan that would work in practice. The functionaries in AEP, however, strongly preferred to focus the consultation process around neighborhood residents. In a technical sense, it was much easier to convoke neighbors than to design methods of reaching the “floating” population (población flotante) that we discovered makes up the majority of park users. From a political angle, however, neighbors were also easier to control and, if necessary, to placate. Unlike the floating population, once organized they could also be mobilized as a political resource for future projects. On the other hand, listening to all the park’s users meant entertaining the possibility that different groups could have contradictory ideas about and interests in the space, which would then have to be mediated (and which were not likely to correspond with the plans AEP was rumored to have all sewn up already).

Construction worker napping on his lunch break. Rapid gentrification has led to an increased number of large construction projects in the neighborhood.

What TPB viewed as an opportunity to generate a deeper understanding of the complexity of public space, and its multiple potentialities, AEP apparently saw as a dangerous political risk. In the next post, we’ll look at the historical and social forces that make Pushkin Park such an interesting and important challenge for participatory planning.