Aron Lesser Chats with Lorenzo Rocha about Public Spaces and Urban Planning Trends in Mexico City

Lorenzo Rocha is an architect focused on the experimental use of urban spaces. Lorenzo has published two books, Essays on Photography and Architecture (Diamantina, 2011) and Arquitectura Crítica: Proyectos con espíritu inconformista (Turner, 2018), and contributes regularly to the Milenio newspaper. He currently works as a researcher at the Instituto de Estudios Críticos 17.

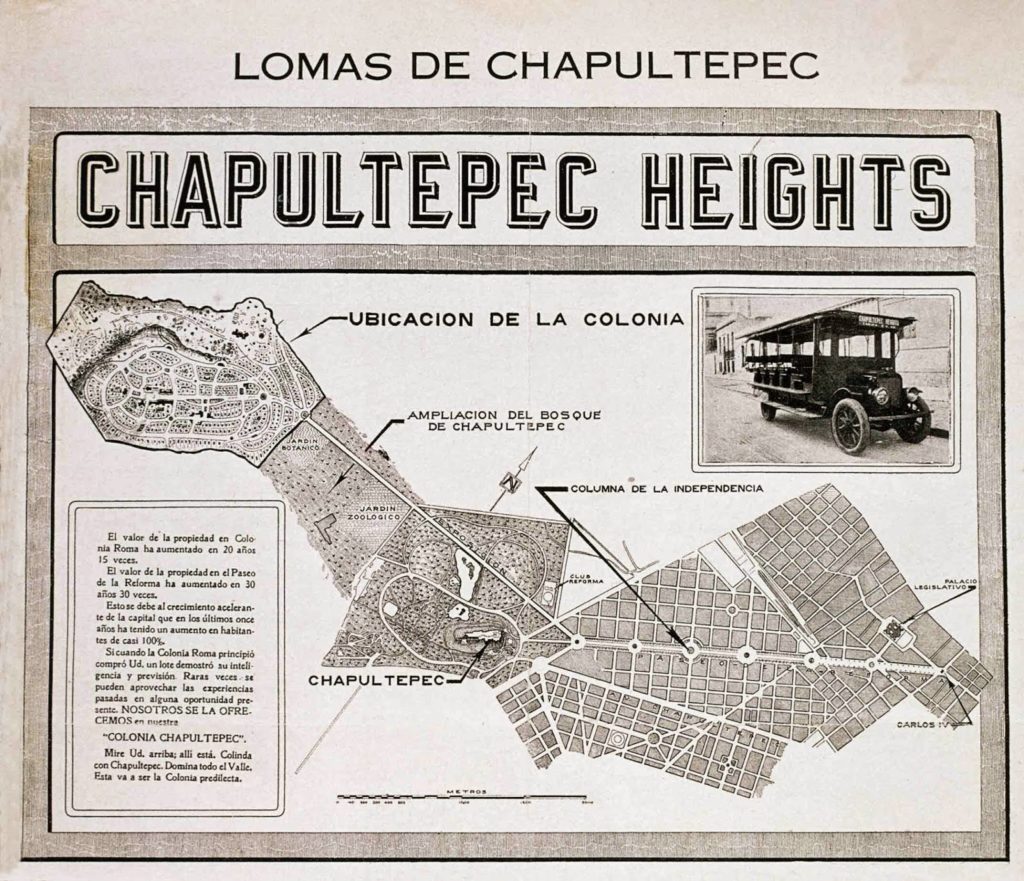

Q: Your recent article focuses on the De la Lama y Basurto company’s development of three well-known neighborhoods in Mexico City between 1920 and 1945. You trace the urban planning histories of Condesa, Polanco, and Lomas De Chapultepec and consider the theoretical perspectives that influenced their designs, paying close attention to parks and other public spaces. Why did you decide to focus your analysis on the relationship between public and private spaces? Why did you focus on these three neighborhoods in particular?

A: I am interested in the “House-city” complex, a neighborhood design in which private space is minimal because it is completed by public open areas like parks, streets, and squares. I have lived most of my life in two of the three neighborhoods discussed in the text. I have experienced firsthand the rich diversity and community atmospheres made possible by the urban and architectural designs of this period, ones which have not yet been paralleled by more recent projects. I also lived in Los Angeles for a year and in the article explore Rudolf Schindler’s architecture, which is from the same period as and followed similar precepts to the neighborhoods discussed in Mexico City. In LA, many of his houses were built in the neighborhoods of West Hollywood, Mid-Wilshire, and Silver Lake.

Q: In your opinion, what influence does the design of each neighborhood have on the ways in which residents and non-residents interact with those spaces today? Have more recent developments altered the built or lived fabrics of these neighborhoods?

A: The design of an open neighborhood enhances contact between people from different origins and social backgrounds. In areas like Condesa, Polanco, and Lomas de Chapultepec, residents frequently interact with non-residents, albeit to different degrees in each. Some might perceive these types of neighborhoods as less “safe” than the monocultural life in new gated communities, but it is indeed a richer kind of social interaction that contributes to a strengthened community and urban experience.

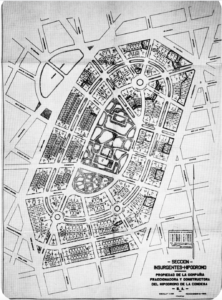

“In the beginning the developers and urban planners followed Ebenezer Howard’s “Garden City” paradigm, established in 1898. The architect José Luis Cuevas was in charge of the design of the Hipódromo-Condesa neighborhood, which incorporates the old horse-race track on the site, closed in the 1920ʼs, into its design. The center of the old track persists as a green area and park today. From this oval, another smaller circular parks and roundabouts were traced in order to build apartments buildings with commercial space with access to the public open areas.”

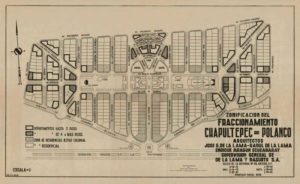

“Less than two decades later, in 1938, the Company started the subdivision for the Polanco-Chapultepec neighborhood. The plan for this neighborhood lays out a central rectangular park (“Parque de los Espejos”, now renamed “Lincoln Park”), surrounded by apartment buildings. The neighborhood included wide avenues lined with tall trees on the sidewalks and parterres, intended for the construction of larger houses. The ratio between public and private space was reduced from the previous design in the Condesa neighborhood.”

“A change in design is clearly visible in the next project developed by the Company, Lomas de Chapultepec (Chapultepec Heights), designed also by Cuevas. There is an obvious influence of the new American suburban paradigm. The neighborhood was designed with large residential lots, resembling the countryside, exclusively for big single-family houses with private gardens. Although the neighborhood has wide avenues lined with trees and central parterres, there are almost no public green spaces or parks. It prioritizes private over public land use. Slowly, and boosted by growing crime rates, this approach has informed the development of Gated Communities in Mexico City.”

Q: You state that you wrote your piece from a social activism lens, rather than, for example, a post-critical architectural one. What were your motives for writing this article and why did you employ an analytical approach rooted in social activism? What implications for spatial justice and equitable urban development does your research have?

A: The text is part of a collection of notes for an ongoing seminar conducted on-line at the Critical Studies institute 17 in Mexico City. The particular selection for these notes is intended to contribute with a philosophical approach to discussions about Mexican cities. Social activism provides a sociological perspective to any architectural discussion. This is in turn essential when assuming a critical standpoint, for architecture that does not place people at the center of its interests cannot be critical.

Q: Mexico City in many ways is undergoing a building boom. What current urban development and architectural trends do you see contemporary developers employing in Mexico City? How are these similar to and different from those in the neighborhoods that you analyze in your piece?

A: Currently there are two main trends in Mexico City’s urban development. The first one is an outstanding re-densification of traditional neighborhoods in central areas and the second is the vast creation of new land subdivision in peripheral zones both for affordable or expensive housing. The densification process, that affects the three neighborhoods referred to in the text, takes advantage of preexisting conditions to generate value by designing taller buildings in the traditional urban fabric, further diversifying them. The new peripheral neighborhoods are generally monocultural and dependent on private and public mobility. They are the answer to our massive necessity of housing and security, which the original urban fabric can no longer provide.

Q: You bring up COVID-19 in this article’s conclusion and in your recent Milenio op-eds. How do you think COVID-19 may change the ways architects and urban planners think about public and common spaces in Mexico City?

A: The COVID-19 pandemic will most likely have a moderate impact on Mexican architecture and city planning. Probably outdoor spaces, like terraces, balconies and gardens will be more appreciated by the public who can afford them. Yet housing production still does not have enough freedom from economic pressures to become more experimental. Hopefully the current crisis will trigger a more critical attitude among Mexican architects, who up to now have been condescending with all of the urban developers’ policies. Perhaps in the long run, some aspects of today’s pandemic behavior will become permanent. Hopefully it will be the positive ones, like working and studying from home and the consequent reduction in mobility, but that is impossible to predict.

The full article in Spanish and an English excerpt are available here